A former resident of the Institute for Advanced Study in Nantes and patron of the Chair Arts, Societies and Contemporary Transformations, Souleymane Bachir Diagne has published The Universals of the Louvre (Albin Michel, 2025). Drawing on the museum as a starting point, the philosopher examines the idea of the universal as a living process, shaped by history, cultural circulations, and tensions inherited from the colonial past. The article that follows offers a reading of the book by Sophie Halart, Director of the Institute.

In The Universals of the Louvre (Albin Michel, 2025), former associate member of the Institute and Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne offers far more than a reflection on an emblematic museum institution. He undertakes a philosophical meditation on the universal itself: not as a given, stable, overarching horizon, but as a relational process—shaped by history, violence, displacement and translation, which together constitute our shared worlds. The Louvre thus becomes a concrete, conflict-laden and historically charged site from which to rethink what it might still mean to “make the universal” today.

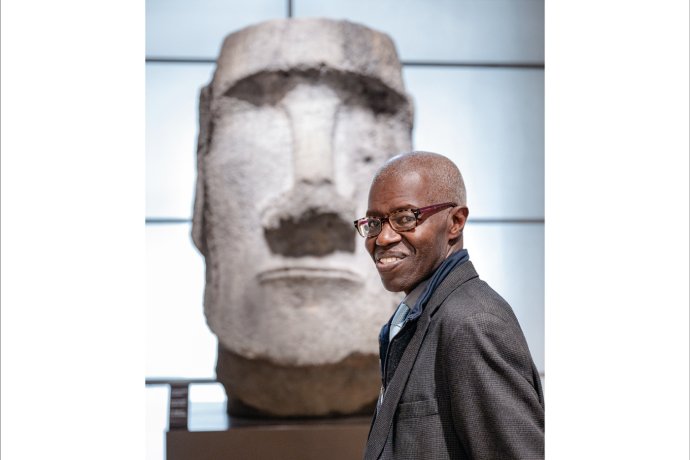

One of the book’s central conceptual gestures lies in its interrogation of what Bachir Diagne—without a touch of critical irony—calls “Louvrization”: the process by which works originating in other cultural worlds enter the universal museum, gaining unprecedented visibility and recognition, often at the cost of being torn from their own histories. Louvrization is understood as an ambivalent historical fact, calling for a reading attentive both to the colonial violence that made such circulations possible and to the creative forces these works continue to carry and activate.

This is where the decisive notion of sharing comes into play, understood in all its ambivalence. To share works is not to pacify them or neutralize them within a consensual narrative of humanity. The works thus shared are not silent witnesses to a benevolent universality: they bear within them the memory of relations of domination that brought them to the museum, while also manifesting a creative power that has profoundly shaped—and continues to shape—artistic modernities. They are not simply received into the universal; they actively contribute to forging it.

This idea leads Bachir Diagne to formulate a strong thesis: works of art are not survivors, but forces of mutation—“mutants,” to use his term—endowed with genuine agency. They act, displace and transform the interpretative frameworks in which they are inscribed. The museum thus ceases to be a site of closure or culmination; it becomes a process, a space of circulation, confrontation and translation, always unfinished.

From this perspective, artworks appear as “living rhizomes”: they are not fixed in a single origin or stable meaning, but unfold multiple ramifications across places, times and perspectives. Here Bachir Diagne draws on the ontology of Léopold Sédar Senghor, for whom being—existing—is a force of life. Whether human, animal, vegetal or mineral, beings are defined by the force they express, by a moving reality that the artist makes perceptible, freeing things from their confinement within appearances.

It is within this framework that the question of restitution emerges—not as an automatic answer or a uniform imperative, but as an unavoidable issue for thinking through contemporary conditions of sharing and recognition. Restitution compels us to hold together the past—and the colonial violence that shaped museum collections—and the possible futures of artworks, museums and relations between societies. In this sense, restitution participates in a conception of the universal as a dialogical force: historically constituted, yet open to multiple becomings.

The universals Bachir Diagne speaks of are therefore neither abstract nor disembodied. They are made in relation, through openness, dialogue and sometimes conflict. To think the universal in this way is to accept that it is never given once and for all, but always in the making.